- Home

- Meg Vandermerwe

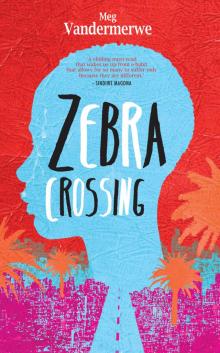

Zebra Crossing Page 7

Zebra Crossing Read online

Page 7

Two years later, I found out the hard way the real reason we didn’t go.

George had gone to church for the first time a few years earlier. It was Auntie Ruth, Mama’s eldest sister, who convinced Mama to send him.

‘All the children go to church. Do you want your children to stick out like sore thumbs even more than they already do? Come, send the boy for the blessing of becoming a young adult.’

The blessing of the young adult was a special ceremony that took place at Auntie Ruth’s church. When children turned twelve it was the custom for them to be specially blessed by the pastor as a mark of their entry into young adulthood.

I was sick in bed with stomach ache that day. Mama stayed home to care for me, and Auntie Ruth took George. So I wasn’t there to see it. But when George came home in his suit, carrying a slice of cake wrapped in a piece of newspaper, he said it was ‘all right’.

The morning before we went to church for my blessing, Mama washed me from head to toe and combed my hair down with hair cream. George wanted to shave his head to look like Tupac, but Mama cuffed his ears and told him sharply to put on his school tie and stop his games.

Because we were not members of our own church, we were going to Auntie Ruth’s, where a new pastor had recently joined the congregation. I looked in Mama’s bedroom mirror as she tied a white ribbon into my hair.

‘You look very pretty,’ she said and kissed the top of my head.

‘Come, George, turn off that television. Today we are churchgoers.’

It seemed to start fine. Not too many looks as we slipped into the three seats next to Auntie Ruth, Uncle John and their three boys. Auntie Ruth’s youngest stuck his tongue out at me, but I was used to that. We all rose to sing with the choir. Then sat again to listen to the pastor’s sermon, which was all about temptation.

‘The Dev-il comes in all guises, my brothers and sisters. Yes, he is a master of temp-ta-tions! Wine and women. Wine that dulls the senses and creates for lax morals. Women who tempt us into siiiin with their charms.’

Mama shifted uncomfortably like she was sitting on a heap of termites, but kept her face calm and her hands folded around the purse in her lap.

The sermon went on for a very long time, and if it wasn’t for the pastor’s habit of raising his voice at the end of each sentence until his voice boomed, demolishing our private thoughts, I think more men than Uncle John would have nodded off. Poor man. Every time he bowed his head and began to snore, Auntie Ruth would give him a violent elbow jab in the ribs so that his head would pop up like a frightened horse.

Finally, it was time for the children who were to receive their first special blessing to make their way to the front. The middle aisle filled with boys and girls all dressed in white. Some were holding flowers, like brides. Today their souls are marrying Jesus Christ, said Auntie Ruth.

‘Go on,’ Mama whispered, and she gently nudged me from the seat, ‘it will be all right.’

Auntie Ruth was beaming like she had just won the lottery. She was a great believer, and was perhaps hoping that if all went well her wayward sister might become one of the saved.

‘Go on, go on.’ With a flick of her wrist she encouraged me to join the back of the queue.

On the way to the church, I had heard Mama quiz Auntie Ruth again about the proceedings.

‘You are certain he knows the situation?’

‘I already told you. He knows everything.’

‘But you haven’t yet told me what he said.’

‘Nothing.’

‘Nothing?’

‘I have already told you, sister. When I told him about Chipo, he asked about your marriage…’

‘What has my marriage got to do with anything?’

‘I do not know. But he said Chipo could come. That is the most important thing. He is a good man, Grace. A kind man. Do not worry.’

One. The next. Another. As I edged up the aisle behind the other children I could feel the eyes of all upon me. I turned back to look at Mama, who was watching me anxiously. It was just me left. The other children had returned to their seats. I knelt at the altar and closed my eyes as Mama had told me to do. But no blessing came.

‘Stop! Stop stop stop!’ the pastor called. I suppose he had been waiting for this moment. The choir fell silent. The congregation held its collective breath.

‘Stand up, girl.’

Awkwardly, I got up.

‘Stand and face the congregation.’

I did as he commanded. I could see that Mama wanted to rise, but Auntie Ruth was telling her to stay where she was.

‘You see this girl? I was visited in a dream…’ the pastor began, ‘a dream, my friends, and in that dream the message was clear. She bears the mark of the sope. It is a curse.’

The congregation gasped, Mama and Auntie Ruth included, but the pastor raised his hands for quiet.

‘A curse that signifies the sins of her parents. The curse of the mother shall be visited upon the offspring. As much as Cain’s mark branded him as one cursed by God.’

The pastor fell silent for a moment. What was he talking about? I did not know. All I knew was that there would be no blessing for me.

‘She must repent and the ancestors be properly appeased. Let us pray together.’

The pastor pushed me down onto my knees. The congregation was still deathly silent. Without a moment’s hesitation, Mama stood up. She pushed past her fellow congregants, who sat rigid as useless boulders, and marched to the front. She picked me up and jerked my brother by the arm from his seat before marching us outside.

Back home, my brother was only too happy to be allowed to play with his soccer ball in the street. Mama didn’t even make him change out of his suit first. Meanwhile, Mama soothed me, rocking me close as I sobbed. I could smell her Oil of Olay, but its familiar scent offered no comfort.

Do not cry, she told me. They had once done such a thing to a friend of hers, too.

‘What friend, Mama?’ I sniffed.

‘You don’t know her. She no longer lives here.’

‘Where does she live?’

‘Eh, she lives in Porttown, last I heard – do you want to hear the story or not?’

I nodded.

‘After two years of marriage she had yet to produce a child. Her husband, a religious man, had insisted that they go and pray for help. In the church every Sunday, this friend, she stood as members of the congregation and the pastor and her husband laid hands on her and spoke in tongues demanding that the demon that was filling her womb with concrete be driven out.’

‘Did it work?’

My mother shook her head. ‘No. Eventually she refused to go with her husband, who left her, calling her a mhanje. That’s the word in our culture for the lowest form of womanhood, a barren woman. But there is a happy end to the story. She married again and now has four children, last I heard.’

Mama stood up. ‘That pastor is a self-righteous, superstitious idiot. When he talks it is like watching a pot of porridge bubble with hot air. I should never have listened to Auntie Ruth. When he asked about your father, I should have known that he was planning monkey business. Come, no tears. Let’s watch that match between Manchester and Tottenham. We will find a new church.’ Mama would never return to any church.

But I was angry at her that morning. If she knew that people were like that, how could she have let me go into the viper’s nest?

‘You must get strong. If you wait for others to do good by you, you will be waiting a long time. Believe me, I know it. Besides, do not think that God isn’t watching them and taking account.’

And then, in a softer voice, she told me to go and fetch the bottle of lotion in the bedroom. Undoing the buttons at the back of my dress, she rubbed the lotion into my skin.

As I watch David tying string around the tshangani bag, making it ready for collection, I wonder if he still remembers that day, so many years ago? And Margaret? I do not like the thought of David or his sister feeling sorry for

me. I go to the window and look out. Below, a white woman is walking with a child and an old bakkie is struggling to park while the other motorists hoot.

Church or no church, I want our first Christmas in Cape Town to be special, like it used to be with Mama. When it approaches, I decide to make chicken, cabbage salad and rice, just like Mama used to at home. There is plenty to celebrate, I told George a few days earlier. For one thing, it was the first time in four years that we could afford such a meal.

‘Ha,’ George said, ‘so you think we are rich?’ But he and the others agreed.

Outside, I can see that the bars and restaurants are making their final preparations for the Christmas festivities too. A girl with spiky pink hair at the Billabong shop is sticking pictures of snowmen and snowflakes in the window, even though Christmas comes at the height of summer here. ‘Season’s Greetings’ is what most of the shop windows say.

When I was at school and we were given Charles Dickens to read, I wondered what it would be like to see and taste snow. Mama had distant cousins who lived in the north of England, in Newcastle. One year they sent us a photograph of them all standing holding lumps of ice in the palms of their hands. In England it snows often, Mama told me. At the time I held the photo under my nose and squinted from the snow to my cousins’ amused eyes, back to the snow.

Secretly, I knew that Mama dreamt of one day visiting Great Britain. In particular, I knew it was her wish to make her way to Manchester and see the real Old Trafford, where her favourite team played.

I wish I could have been the one to enable such a visit. I am thinking such thoughts as I make my way into the Mountain Dew Superette.

The Mountain Dew Superette is always dark and cool, even on hot summer days. Superette sounds like we do not sweat. There is never a fan to cool the sweating face of the Somali owner, like in our tin-roofed spazas back home. Inside, the Somalis sell tired fruit and vegetables: oranges, apples, onions, potatoes. Packets of Marie and Tennis biscuits. Toilet paper – single ply. Newspapers. Magazines – You and TV Guide. Bleach for cleaning toilets and sinks. Green Sunlight liquid for washing pots and dishes. Ricoffee. Sugar. Long-life milk. Tea. Because it is open twenty-four hours, there are times you can go there, such as very early in the morning, and guarantee that it will be quiet.

I am here to get ingredients for our Christmas lunch. I buy rice. Cooking oil. Two onions. Two heads of cabbage. For the chicken I will have to walk to the Spar on Kloof Street.

On Christmas Day itself, I wear the red skirt David admires and prepare the meal with great care.

‘See,’ says George, patting his swollen belly after his first two helpings. ‘Life is not so bad here after all. And, what’s more, there are only, what, forty-eight weeks until the WC.’

‘Don’t say WC. It sounds like you are talking about the toilet, not the World Cup,’ David jokes.

Peter bursts into laughter and spits out his cabbage.

I have been watching David eat.

‘Is it all right?’ I ask as he hands me his plate for extra rice.

‘Delicious, Chipo, as always.’

‘Oooooh, David, you know I always cook so delicious just for you.’

George. I glare at my brother. I do not care what he says. He can do nothing to dampen my mood. With ease and grace I serve David another large spoonful. Today at least I am the proper woman of this house.

After I serve the others, I decide I will take Jean-Paul a plate of food too. His door is closed, so I know to knock before entering. Why is it that he never seems to have any visitors, apart from clients? And why does he never seem to go out? Does he not have someone with whom to spend Christmas?

‘Va Jean-Paul?’

No answer. I try again.

‘Va Jean-Paul, it is me. I have some Christmas lunch for you. Chicken and rice. It is still warm.’

The door opens. Jean-Paul is wearing a long robe. He looks like a pastor.

‘What is it? I am occupied.’ I peer into the room. It is empty and dark and smells of sweat and heat. I hold out the plate.

‘No, thank you, Chipo. I must go.’

I go back to the table, where the others are still talking and eating. My brother is helping himself to the last scrapings from the pot.

‘What’s going on with Mr Congo? Too good for our food?’

‘He has already eaten,’ I lie. I pass the plate to my brother who, using his fork, divides the portion between himself, Peter and David.

‘You know, perhaps Jean-Paul is the wisest one. At least he works for himself. He doesn’t rely on anyone else for a job.’ That is Peter. He has been drinking beer all afternoon since coming home from church and is in a merry mood.

My brother belches. ‘Master? Ha! If I was his customer I wouldn’t let my backside leave the wall. Have you noticed how he never has a woman? It’s not natural.’

Peter nods his agreement and raises his beer bottle to his lips. David says nothing.

‘At least you know your sister is safe with him,’ says Peter, spooning the last of the food into his mouth. ‘And he pays the largest share of the rent,’ he reminds the others, his eyes now foggy from alcohol. ‘Let us not forget that. Even if he is a Buttock Beak.’

David frowns but Peter laughs and shakes his head.

George looks at me. His eyes struggle to focus. I can see he is drunk too. ‘Ha ha. Chipo’s friend. A Buttock Beak…’

Peter points his hand at David as though it is a gun and takes aim. ‘You hear that, brother? Buttock Beak, bang bang!’

There is a woman. Every morning I watch her from the window. She leaves President’s Heights at six-thirty and returns again in the evening, sometimes as late as eight. Sometimes she is carrying a small blue plastic bag from the Mountain Dew Superette. Sometimes not. Sometimes she carries a faded black umbrella, sometimes not. She always wears a black cardigan. Her skin is dark. Very dark. I do not think she is from Zimbabwe. Is she from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, like Jean-Paul? Or Cameroon? Nigeria? Could even be Mozambique. She looks George’s age, or perhaps a few years older. Over her shoulder a black handbag hangs limply. It looks empty. No matter what the weather, this woman walks with her shoulders hunched. It looks like she is always cold. Is she cold? Why is this woman always alone?

Every day I watch her while I wait for the water to boil for George’s tea and again when I am washing up after preparing dinner. She does not know that I am watching her. I know that we will probably never meet, but I want to ask her, ‘What’s your name?’ and ‘Where do you come from?’

Nine

‘Turn.’ Jean-Paul circles around me. ‘These Somali boys are so thin. Don’t fidget, please, Chipo. Don’t know what their mothers and grandmothers feed them. Mussolini’s spaghetti.’

He laughs, and then stops abruptly, as if laughter were a sin.

I am wearing a blazer Jean-Paul has been given to alter in time for the start of the new secondary-school year in January, in three days’ time. I was there when the mother arrived. Mrs Shire, wife of Mohammed, the manager of the Mountain Dew Superette, wearing her black hijab. Her son had got into Gardens Commercial High School. This apparently is something to celebrate, as not just anyone can get in, even though it is a government school. You have to be good at science or maths. Her son stood looking embarrassed as his mother continued her boasting. ‘Sleeves too long,’ she said. She had bought it second-hand. ‘You fix.’

Jean-Paul nods to indicate I am to take the blazer off. It is ready to be delivered.

‘Jean-Paul, is it true about the man who starved to death waiting for his asylum papers?’ I do not want to make my new friend uncomfortable, but I had not been able to get the image of that poor man out of my head these past months, and I did not know who else to ask.

Jean-Paul takes the pins from his mouth and slowly puts them back in their tin. He sighs.

‘It is. He used to live right here in President’s Heights…’

I had already heard this from Peter a

nd David.

‘Do you believe in fantômes, Chipo?’

‘Fantômes?’

Jean-Paul hangs the blazer on a wire hanger. ‘You know, the spirits of the dead. The ones that won’t go away.’

‘Oh, a ghost.’

‘Yes yes, a ghost. They say his ghost still haunts this place. I can believe it. You see, it does not know what to do. It died far from home and its own people. It is a fantôme caught between home and here, between this world and the next. Very bad.’

Very bad. This, I will learn, is what Jean-Paul says when a story is too terrible to tell. Very very bad. Bad. Sad. Mad.

‘And he is not the only one, you know. Not the only ghost we have living here.’ Jean-Paul glances in the direction of the photograph. ‘Still, at least his family know where he is. It is worse not to. Not to know.’

I look at the photograph too. Today there is a new bunch of pink roses next to it, and two statues of the Virgin Mary stand guard on either side.

I want to ask Jean-Paul about the woman and child in the photograph. I do not yet possess the courage. Who are they? His wife and daughter? Why aren’t they here with him? When was the photo taken? I know that Jean-Paul sees me looking, but he pretends not to.

‘Take this blazer downstairs, Chipo. Mr Mohammed is expecting it. And please bring me back one orange.’

Making clothing takes time and effort. But it can make a big difference to people’s lives. That is what Jean-Paul tells me. He always injects some of the personality of his clients into the items. That is why his customers are so satisfied.

‘For example, that lady who came last week, Chipo. The one with the scar here…’ Jean-Paul points to his cheek.

I nod. I know the one.

‘I saw, in spite of her serious appearance, she has a lighter character. Meaning she is more joyful. So I included a bow on each sleeve. She did not ask me for one, but when she saw it, was she not thrilled?’

It is true. She was. I nod again. When Jean-Paul says ‘thrilled’, it sounds like ‘trilled’. He hardly ever pronounces his h’s. Must be how people speak English in the Congo, I tell myself.

Zebra Crossing

Zebra Crossing