- Home

- Meg Vandermerwe

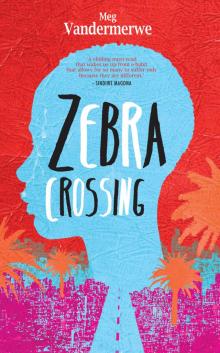

Zebra Crossing

Zebra Crossing Read online

ZEBRA CROSSING

ZEBRA CROSSING

MEG VANDERMERWE

A Oneworld Book

First published in North America, Great Britain and

Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2014

This ebook edition published in 2014

Originally published in South Africa by Umuzi, an

imprint of Random House Stuik (Pty) Ltd, 2013

Copyright © Meg Vandermerwe 2013

The moral right of Meg Vandermerwe to be identified as the

Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-430-8

ISBN 978-1-78074-431-5 (eBook)

This is a work of fiction. While, as in all fiction, the literary

perceptions and insights are based on experience, all

names, characters, places and incidents either are products

of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Stay up to date with the latest books,

special offers, and exclusive content from

Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

Joy and gladness will be found there,

thanksgiving and the voice of song.

OLD TESTAMENT

We tell stories not to die of life.

ANTJIE KROG

For Sumarie: for your love without borders

For Selma Friedland (in blessed memory)

Contents

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Prologue

THE PRESENT

‘Tell me, learners, what is a border?’

For some, dawn is the loneliest time. But not for me. I rise with the living, the sun and the rock pigeons’ chorus. I watch the light dress rooftops, car parks and, beyond them, the mountain. Then it comes: memory. You see, even after all that has happened to me, I still have my past for company. It creeps out of dark corners and gathers round like specks of slowly spinning dust. Familiar faces and places return. And those questions that still demand answers.

‘Tell me, learners…’

Late 1990s. Primary school. Zimbabwe. I am seven. Our headmaster, Va Pfende, teaches us that Africa’s borders were drawn many years ago. Va Pfende was a veteran of the war of independence in the 1970s and he likes everyone to know it. Using a bamboo stick, he points to the map of Africa that hangs on the classroom wall below a portrait of our President.

‘It was the imperialist murungu,’ our headmaster explains, ‘he came long ago, dividing this continent like the carcass of an ox, and kept the lion’s share for himself. Remember, pupils, matsoti haagerane. There is no honour among thieves. Thankfully, our great Zimbabwe is now independent. But never forget: once your parents and grandparents were slaves to greedy foreigners.’

As the sunlight hits the shop windows, so that triangles of gold appear in their panes, I recall how obediently we scribbled down ‘greedy foreigners’, pledging to commit Va Pfende’s words to heart in case Ian Smith and the other British colonialists, like locusts, ever threatened to return.

On that classroom map, national borders were drawn in purple. When my brother George and I reached the border at Musina, it was too dark to see whether those purple lines existed in real life. But since that September night, I have crossed that and other borders many times. Flown so high above them that below looked like an infant’s patchwork puzzle. Flown so low that I could smell the dust and see the dry seeds waiting patiently for the rains to come and split them open. On those journeys I have seen that, in reality, no borderlines are tattooed across this earth. Forests and valleys, deserts and rivers, they know nothing of borders. Instead, they exist only in the minds of politicians, who guard their man-made borders with soldiers in uniform, wearing black boots and carrying clipboards and ak-47s.

‘What is a border, learners?’

If I were in that classroom today, I would raise my hand and answer: a border is a place where barbed wire and high fences block your way.

It is where you are not wanted, but where you must nonetheless go.

It is where you must wait, terrified as you are, for the right moment to take your chance and dance with fate, while high above you in the starlit sky, the migrating swallows pass back and forth unhindered.

A border is where you must say goodbye. You cannot afford to turn and look back. The past is the past. That is what your brother says.

Borders rhymes with orders. You follow your brother’s orders. You have no choice. Time to go forward, he says. To look forward.

A border is where you swap home for hope.

One

BEITBRIDGE, ZIMBABWE

SEPTEMBER 2009

Four in the afternoon. George should be in the main house, squeezing a jug of mango juice or whatnot for our mistress. She will be where she is every afternoon after another beauty treatment at Mrs Mabeeni’s parlour – in the sitting room, curled up on the leather sofa like a pampered pet, watching satellite television or flicking through Cosmopolitan magazine while eating Choice Assorted Biscuits. But instead he has come to see me in the outside courtyard, where I am wringing out the mop.

He knocks a cigarette from its pack and slips it between his lips. His face is sour. So, a dark mood. Another row with Mai Mavis, the cook? I know better than to ask. Must wait. Wait patiently until he decides to tell me. My brother sucks in, and then blows out.

‘This time she has gone too far…’

I notice his hand is trembling.

‘I won’t protect her. I will confess to everything.’

Confess? He pulls on his cigarette. A cloud of smoke.

‘I mean, did I not do only as she told me to? Should I now be punished for that bitch’s stupidity?’

I listen. Little sister. I am seventeen. It is my job to listen. When I am not scrubbing, or sweeping. But most of all it is my job to obey. If I do not obey, how can he protect me?

The General’s third wife is young enough to be his daughter. She and the General have been married for one year, ever since Mr General divorced Wife Number Two, and promoted this wife from being his ‘small house’ – his mistress. Wife Number Three has it all – youth, beauty and an education, but it is true that, since their marriage, the General’s attentions have once again begun to wander. There is gossip among the servants. He is courting the flirtatious Miss Patience. He is interested in Miss Hazel, a woman with round, jiggling breasts and questionable morality.

But now, new developments, my brother says. So perturbed is he that he can hardly articulate his words. Wife Number Three has been caught red-handed in another man’s bed. George swallows. She is in serious shit with the General.

‘Before the day is through, he will interview all of us. He is certain she could not have managed it without the servants’ help. We will be interrogated, then dismi

ssed.’

My brother drops his cigarette stub and, his hand shaking, immediately lights another. Then he begins to pace. I know he colluded with our mistress. All the servants did. George often complained that they had no choice. They wanted to keep their jobs. But what now? Hayiwa? George looks desperate. The General is a rich and influential man in Beitbridge. He will see to it that my brother cannot find another job.

‘And to make matters only worse,’ George says, gesturing to me as though to a blocked toilet or some other annoyance, ‘you know how they feel about peeled potatoes like yourself…’

Peeled potato. That is what many in Zimbabwe call me. Also ‘monkey’ and ‘sope’. There are other names, too, depending where you go. Name rhymes with shame. In Malawi, they call us ‘biri’. They whisper that we are linked to witchcraft. In Tanzania, we are ‘animal’ or ‘ghost’ or ‘white medicine’. Their witch doctors will pay handsomely for our limbs. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, they call us ‘ndundu’ – living dead. If a fisherman goes missing, they call on us to find the body. In Lesotho, we are ‘leshane’, meaning half-persons, whereas to South Africans, depending on whether they are Xhosa or coloured, we are ‘inkawu’, meaning ape, ‘wit kaffir’, ‘spierwit’ or ‘wit Boer’. Meanwhile, my brother calls me ‘Tortoise’. He says I always perform my tasks too slowly. Sometimes, though, I am ‘Little Sister’. All the whites in these places simply call people like myself ‘albino’. I also have a real name, though. My name is Chipo. In Shona it means ‘gift’. When my mother gave it to me, I wonder, did she have a premonition about her daughter’s destiny?

‘Oh, to hell with them all,’ George says finally. His mood has changed. Storm clouds are brewing in his head. He drops the stub of his second cigarette and twists it under his shoe.

‘Put away that mop and gather your things. We’re going home early, Tortoise.’

‘In South Africa there are plenty of jobs,’ George says. ‘We won’t have to crawl on our hands and knees to earn a pittance. And they have proper hospitals and shops crammed with cool goods like flatscreen TVs, and all the roads are clean, paved – not these bloody moon craters. That is because in South Africa…’

On the opposite pavement a woman is selling delicious, roasted sweet potatoes smelling of caramel. A few years ago those potatoes would have sold in moments. But money is tight for everyone these days, and what was once a small treat has become an unaffordable luxury for most. I watch her poke at them with a fork as George repeats the same promises about life over the border that he has been reciting to me daily since Mama passed away three years ago. I say nothing. My stomach grumbles from hunger and I pull my umbrella lower to protect my eyes. My spectacles have steamed up. It is too hot even to think. A stray dog trots past, one of those location specials, a little bit of every breed. Its tan-coloured ears and tail are pointing upwards, its red tongue is hanging out and its ribcage makes me think of prison bars. Sometimes these strays are hit by cars. Then their carcasses are left to rot at the roadside. Food for the rats.

I think of the General. Big cats like the General always catch rats like George and me. What will happen? George had to lie and tell the General that we have been called home because our mother is sick – so, an emergency. Otherwise we would not have gotten permission to leave.

‘Bastard. Doesn’t even remember we are orphans.’

We had to leave our week’s wages as proof we would return for our interrogation about our mistress’s lover. George spits. So now we are without a week’s wages. And without jobs. What will tomorrow bring? Had George even thought of that?

If you had passed us in the street that afternoon, could you have known that once we both attended school, like the General’s own teenage children, and had dreams and ambitions of our own? George wanted to start his own business. I secretly hoped one day, somehow, to qualify as a social worker or district nurse. What is more, our mother, when she was still alive, owned a brick house, which, although much smaller than the General’s imposing home, had two bedrooms and an indoor bathroom with a flushing toilet. From that house our mother operated a lucrative drinking tavern called ‘Old Trafford’, named after her beloved Manchester United’s home ground. There, surrounded by posters of David Beckham and Dwight Yorke, she served mazondo, boiled hooves and hard-boiled eggs, as well as a potent home-brewed beer called Seven Days, which caused her patrons to return faithfully time and time again.

A minibus taxi speeds past, its sides smeared with red dust, like chilli powder. Too full for us? Or maybe it is me they do not want to stop for. Two men pass. Too close. I can feel them staring. I look at the ground. My feet in my zhing-zhong flip-flops from the Chinaman shop are red from the dust, too. I must give my toes a good scrub tonight. Not that it matters. We can’t keep the dust out of our house, though the place is never filthy – I make sure of that.

In 2003 the government declared informal drinking taverns like Mama’s illegal. Operation ‘Remove Moral Filth’, they called it. The taverns encourage Zimbabweans to be sinful. That is what the government radio and newspapers shouted. All informal drinking taverns must be demolished. Street markets, too. If you don’t do it, the police told us, then they will.

‘What are you waiting for? Bring your hammers,’ Mama said, standing in front of Old Trafford. Her skin quivered with rage. Maybe she was feeling very brave, or maybe she didn’t believe they would dare to deliver on their bold promises. Either way, I think that if she could have killed that policeman at that moment, she would have. The head policeman had smiled and walked away.

Some say he had seen Mama at the rallies supporting the MDC. That is why she and Old Trafford in particular were targeted. Whatever the reason, one month later to the day we were woken by the rumble of their trucks.

Will we soon be in a truck? I wonder to myself. Jumping the border? Every day, they say, hundreds are doing it. That is what the radio and newspapers tell us. And then what? That truck will carry us from here to…? I look up in the direction of the border, over and beyond. From here to…? I cannot imagine what it looks like, in spite of George’s stories. What does it look like? Johannesburg. Cape Town. They don’t sound or rhyme like anything. Just names. I rub my eyes. They are burning from the heat and the dust. My umbrella is not helping much.

It is true that even before the demolition there were times when Mama admitted, ‘I am not hungry, Chipo’ or, ‘Yo, I feel so, so tired! The tavern is wearing me out!’ But there is no denying that, after it was destroyed, within eighteen months her health took a turn for the worse and so did our fortunes.

‘Tortoise! Pay attention!’ My brother sucks his teeth, irritated. ‘Deaf as well as blind.’

I push up my glasses and lift my umbrella to squint at him.

‘I said you better cook sadza for one extra tonight and buy a bottle of chibuku. I am going to invite Michael to join us. I need his advice about crossing the border.’

Michael is a distant relation of ours, and George’s best friend. They have been best friends since primary-school days. Michael is a car mechanic who often boasts to my brother that he can repair a Toyota Land Cruiser with parts from a tractor. ‘No one would even notice,’ he says. When he was a boy, Michael and his father used to water down bottles of petrol with cooking oil and sell them at the roadside. They did this for three months before they were caught.

Michael works for a garage next to Mr General’s taxi shop. It caters to the many trucks and minibuses passing back and forth, transporting people and goods between Zimbabwe and South Africa. He and George love car talk. But they can also debate for hours about Manchester United – which players are decent, worthy of wearing the red shirt, and who are ‘buckets of shit’. Michael, I know, has no desire to go and ‘try his luck’ in South Africa. He is content where he is, he says. But his cousins, David and Peter, are already there.

David and Peter. Peter and David. Twins, though not identical. Peter can sing. David cannot. Peter likes Coke. David, Fanta Orange. I

remember the first time I saw them at school. I was only six. And I can see them both standing in our yard waiting for George to finish his chores so he could play soccer. Once, Peter called me ugly: ‘She looks like a monkey!’ and David beat him. Then, in 1997, their father lost his job and they moved to Harare.

Another minibus is approaching. George sticks out his hand and it slows to a stop. The hwindi pulls back the sliding door.

‘The General has done us a favour… You will see… We are going just in time. Next year the whole world will want to be in South Africa… The World Cup – that is the what. First time it is being played on African soil.’

The other passengers’ eyes narrow and I choose a seat on my own, next to the window. George slumps down next to me and leans back against the torn seat cover. Soon the minibus is bumping over the potholed road. My buttocks will be black and blue long before we reach our home in Luthumba, I think, as George gives me a rare smile.

‘I’ve heard that David Beckham will be there. Imagine that. I will definitely secure his autograph.’

An old man in a front seat wipes the sweat from his forehead with his sleeve. Another picks his nose.

‘But not you, Tortoise. If he sees you, he would get such a fright he might run away.’ My brother laughs and I can feel the other passengers staring again, so I say nothing.

Mama always said she was Zimbabwe’s most loyal Manchester United supporter – like her father and uncles before her. We never knew Mama’s father. He died before we were born. But, like her father, Mama said, she too believed that United could do no wrong. When David Beckham transferred to Real Madrid, she saw it as a betrayal and took down all the posters of him wearing his red shirt that, until then, had kept watch over our mattress as we slept. Then she mourned.

Some facts and statistics about Manchester United that Mama taught us:

• Manchester United first won the European Cup in 1968.

Zebra Crossing

Zebra Crossing